To Valhalla!

Historical sources on raiding in the Viking Age.

Historically, there were three primary reasons for a raid by Norse vikings: resources such as treasure and slaves, semi-initiation rites and lastly, human nature — some people just want to take what someone else has for their own gain.

We know that raids during the Viking Age were mostly conducted by young men in their teens or early twenties. The Saga of Magnus the Good mentions a military expedition conducted by Magnús ‘góði’ Óláfsson (Magnus ‘the good’ Olafsson) in 1035 AD when he was ten years old:

After Yule Magnus Olafsson began his journey from the East from Novgorod to Ladoga, where he rigged out his ships as soon as the ice was loosened in spring (1035 AD). Arnor, the earls' skald, tells of this in the poem on Magnus:

‘It is no loose report that he,

Who will command on land and sea,

In blood will make his foeman feel

Olaf's sword Hneiter's sharp blue steel.

This generous youth, who scatters gold,

Norway's brave son, but ten years old,

Is rigging ships in Russia's lake,

His crown, with friend's support, to take.’

In spring Magnus sailed from the East to Svithjod. So says Arnor:

‘The young sword-stainer called a Thing,

Where all his men should meet their king:

Heroes who find the eagle food

Before their lord in arms stood.

And now the curved plank of the bow

Cleaves the blue sea; the ocean-plough

By grey winds driven across the main,

Reaches Sigtuna's grassy plain.’

Egils Saga

In Egils Saga, we learn of Egill Skallagrímsson (c. 904-995) who, in his teens with his brother Þórólfr, led a raid at night where they attempted to sneak into a village unnoticed but failed and had to escape from their imprisonment:

‘Þórólfr and Egill stayed that winter with Þórir, and were made much of. But in spring they got ready a large war-ship and gathered men thereto, and in summer they went the eastern way and harried; there won they much wealth and had many battles. They held on even to Courland and made a peace for half a month with the men of the land and traded with them. But when this was ended, then they took to harrying and put in at divers places. One day they put in at the mouth of a large river where there was an extensive forest upon land. They resolved to go up the country, dividing their force into companies of twelve. They went through the wood and it was not long before they came to populated parts. There they plundered and slew men, but the people fled, till at last there was no resistance. But as the day wore on, Þórólfr had the blast sounded to recall his men down to the shore. Then each turned back from where they were into the wood. But when Þórólfr mustered his force, Egill and his company had not come down; and the darkness of night was closing in, so that they could not, as they thought, look for him.’

The saga continues:

‘Now Egill and his twelve had gone through a wood and then saw wide plains and tillage. Hard by them stood a house. For this they made, and when they came there they ran into the house, but could see no one there. They took all the loose chattels that they came upon. There were many rooms, so this took them a long time. But when they came out and away from the house, an armed force was there between them and the wood and attacked them. High palings ran from the house to the wood; to these Egill bade them keep close, that they might not be come at from all sides. They did so. Egill went first, then the rest, one behind the other, so near that none could come between.’

The saga then describes the capture of Egill’s men:

‘The Courlanders attacked them vigorously, but mostly with spears and javelins, not coming to close quarters. Egill's party going forward along the fence did not find out till too late that another line of palings ran along on the other side of the space between narrowing till there was a bend and all progress barred. The Courlanders pursued after them into this pen, while some set on them from without, thrusting javelins and swords through the palings, while others cast clothes on their weapons. Egill's party were wounded, and after that taken, and all bound, and so brought home to the farmhouse.’

Vatnsdœla Saga

In Vatnsdœla Saga, a group of young Norse brothers sneak into a Lapp (Sámi) village in the cover of night and sneak out with the treasure. During wartime, however, raids were also conducted to provoke the enemy. In Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, it is noted that Hákon Sigurðarson raided land owned by Haraldr Blátǫnn (Harald Bluetooth) Gormsson because Harald had betrayed him.

Violence in Viking Raids

In Orkneyinga Saga, we learn of Hálfdan háleggur (Halfdan longleg), one of the sons of Haraldr Hárfagri (Harald Fairhair), who slaughtered a village, looted everything and then burned the village down. He was banished by his own father and then fled north to the Orkneys. After repeating his actions by continually razing villages in the Orkneys, he was captured and blood-eagled by Einarr Rǫgnvaldsson in response.

In the early Viking Age, Scotland was known to be home to some of the worst kinds of Norse raiders, but Harald Fairhair eventually put an end to viking activity when he annexed the land under his rule as explored in Haralds saga hárfagra in Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla.

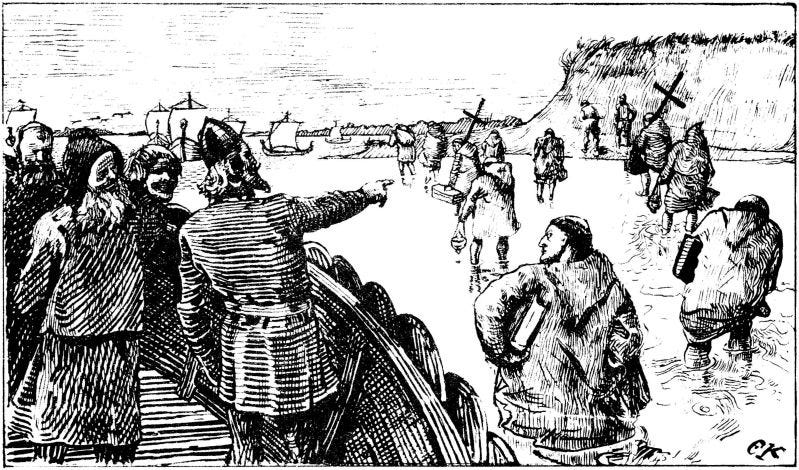

Vikings in England

Contrary to popular belief, England didn’t experience raids to the same extent as other areas across Europe. Most Viking raids were stopped by the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum in 886. The relation England had with Denmark and Norway in the middle to late Viking Age was quite friendly. In Ireland, however, Norse raiders were known to plunder old villages and even tombs, as mentioned in Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib (‘War of the Irish with the Foreigners’) from the corpus of medieval Irish literature. It is also a well-established fact that Dublin was founded by the Norse as the biggest slave port in Northern Europe, and lots of Icelandic settlers had some degree of both Irish and English ancestry because of the slave trade and Christian settlers.

Vikings in France

France by far received the heaviest income of Viking raids. In 845, Paris was besieged by Norse Vikings who were paid to leave. This became a common trend with Vikings in France, as we know the famous Rollo eventually settled in Normandy and became its Duke after a series of Danegeld (‘Dane payment’).